On a Saturday afternoon at the fellowship hall, the stereo blares Southern rock anthems for a flock of Harley riders in leather vests.

Banners on the wall honor veterans, and flags commemorate the Confederacy. A disco ball hovers over a clawfoot tub full of canned beers — two bucks buys you a token and a token gets you a drink from Charlie the bartender.

In one corner of the room, the "Pope" strides across a stage, his voice full of fervor as he auctions off items to the highest bidder. A motorcyclist died recently in a crash and there is money to be raised for the man’s family.

At the fellowship hall, called "Pope’s House," next to the Heart of Fire Church in southeast Louisville, the motto is “when you are here, you are family.”

And today, Danny Ray Johnson, 57, the self-proclaimed pope, bishop and minister to outcasts, really wants you to bid on this gift card to a local tattoo shop.

“I need somebody right now that’ll give me $50 on a $150 tattoo,” he says. “Who will give me $50?”

The Pope, as everyone knows him, commands this side of the room, his voice tinged with the Louisiana drawl of his youth. His biceps are decorated in ink, his sideburns white, his golden pompadour thinning.

Long ago, Johnson fashioned an identity as a modern-day American patriot. Pro-gun, pro-God, pro-life. He talked in 2013 about making America great again. He lamented the lack of God in everyone’s lives. He wept over the country’s future.

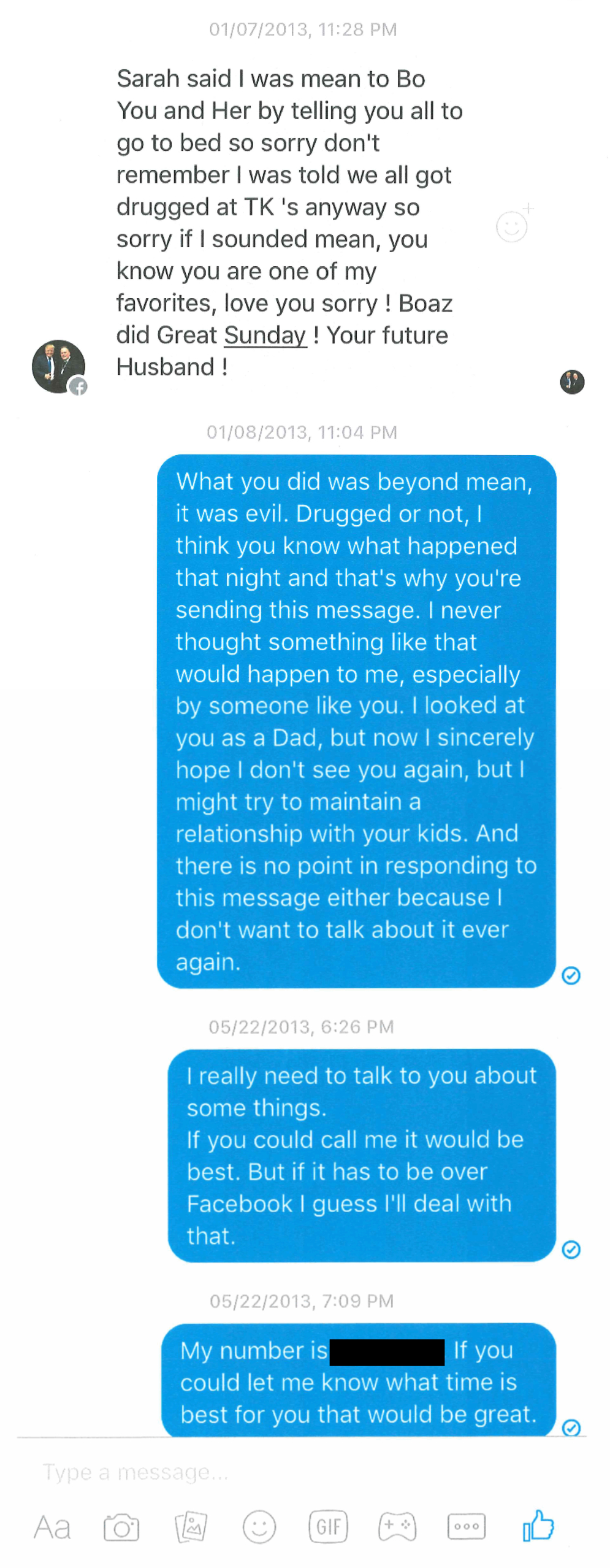

But behind this persona — cultivated, built up and fine-tuned over decades — is a web of lies and deception. A mysterious fire. Attempted arson and false testimony. Alleged molestation in his church.

In Johnson's wake lies a trail of police records and court files, shattered lives and a flagrant disregard for truth.

This seven-month investigation is based on more than 100 interviews and several thousand pages of public documents. It also included numerous attempts to interview Johnson, who refused all requests.

Over and over, there were warning signs for government officials, law enforcement, political leaders and others. Yet, virtually nothing was done. For years, Johnson broke laws. Now, he helps make them.

In his latest feat, Johnson catapulted himself into the Kentucky Capitol in 2016 as representative for the 49th House District.

![]()

To hear him tell it, Johnson has been on stage nearly his whole life. Like Forrest Gump, he just so happens to be in the front row, playing a pivotal role in America’s biggest moments. Time after time. Decade after decade.

He claims he served as White House chaplain to three presidents. A United Nations ambassador. He says he set up the morgue after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and was the pastor who gave last rites for all of those pulled from the towers.

He’s healed the sick and raised the dead. He helped quell the riots in Los Angeles that followed the acquittals of police officers in connection with the beating of Rodney King. He loves people of all races and religions, and he had a seat at the table for international peace talks.

All this despite his history of hate speech, racist Facebook posts and general derision for African-Americans and Muslims. All this, despite his own secrets.

And now, as he paces across the stage at the Pope’s House, Johnson shines, mic in hand, full of passion.

Half of the crowd is focused on Johnson; the other half is interested in beer and the buffet. Johnson’s wife, Rebecca, scans the scene. She spots us.

The church does great work, she says. The Pope is a great man. Why would journalists be skeptical and ask questions?

She points us to the door.

“We know what you’re going to do,” she says. “And you’re going to have blood on your hands. I’m telling you now, it’s the word of the Lord.”

![]()

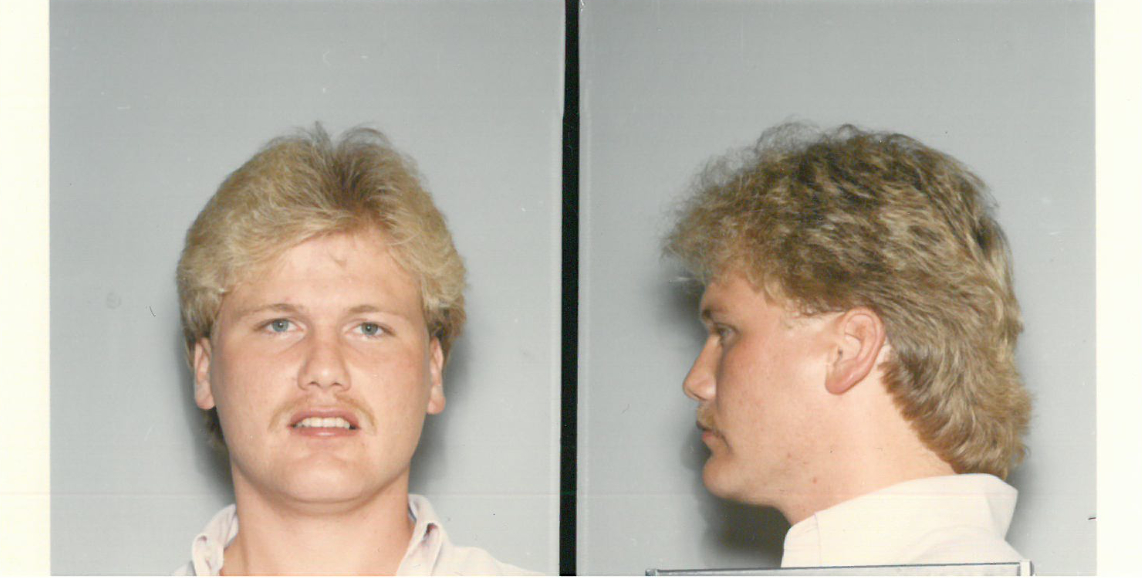

On election night 2016, Johnson reveled in his victory, grinning beneath the glow of a neon beer sign at a favorite local haunt near the church.

Inside T.K.’s Pub, dozens of his friends and supporters crowded up to the bar. This was a big night for Republicans. And it was a huge night, the capstone of a wild political season, for the Pope of Bullitt County.

What led Johnson to dive into politics is anyone’s guess. But in recent years, he had begun to assert himself in right-wing and libertarian circles. He talked freedom and liberty with the same fervor he preached about heaven and hell.

In 2014, he cradled an AK-47 — his “favorite anti-mean government gun” — in an interview with Guns.com.

“Jesus taught us to be armed,” said Johnson. “The real reason for our Second Amendment rights is that we have a gun to keep a mean-spirited government off of us. If they go crazy, we gotta have something to be crazier with.”

He was talking about making America great again before presidential candidate Donald Trump made the phrase his own.

“America is great and it needs to be restored to its greatness,” Johnson said during a 2013 Washington, D.C., rally organized by the arch-conservative, anti-Muslim group Freedom Watch.

At the rally, he was introduced as “Bishop” Dan Johnson and gave the invocation wearing a black suit and a white priest’s collar.

Johnson touted the Tea Party, recounted his heroic role in 9/11 and urged elected officials to “get on their knees, not to Allah, but to God Almighty."

Fast forward to July 2016. Jennifer Stepp had won the May Republican primary for Kentucky’s 49th District seat. But a former county jailer filed a lawsuit questioning her candidacy papers, and a judge declared Stepp ineligible.

Then, the Bullitt County GOP’s executive committee met behind closed doors, pored over four candidates and took a secret ballot. The winner: Danny Ray Johnson, the preacher from the nondenominational Heart of Fire Church.

As a newly minted candidate, Johnson’s platform didn’t skew far from his years-old rhetoric supporting guns, liberty and pro-life causes.

“Pray To Make America Great Again” was the edict on his church’s billboard for Freedom Fest, a political rally held in August 2016 at Heart of Fire.

“It’s never been like this before,” Johnson told hundreds of attendees, his voice cracking. Tears welled in his eyes and he held his thumb and forefinger about an inch apart. “We are so close to losing this freedom.

“Donald Trump, we need you.”

![]()

The only person standing between Johnson and public office was 69-year-old Linda Belcher, a retired schoolteacher, principal and lifelong county resident.

She campaigned on her dedication to public service. Her husband, Larry, had held the 49th District seat for six years before he died in a 2008 car accident. Belcher succeeded him and served three terms. She was the incumbent and a formidable opponent, for sure. But, she was a Democrat in a county that, like many in Kentucky, was becoming increasingly Republican.

Local politics can be combative and personal. Johnson liked to lob verbal bombs at Belcher via Facebook. He skipped the only public debate and canvassing came courtesy of a supporter who drove around a big pickup truck with a Johnson logo.

One Facebook campaign video, shot on a cell phone, opens with Johnson in a military fatigue-style shirt. He stands in front of a flag-draped, military-grade cannon, a piece of artillery the size of a pickup truck.

“Emergency. This is an emergency,” he says, staring into the camera. “We’ve had death threats, we have had bomb threats on our church, bomb threats at our house, our address has been given out, this is happening by lyin’ Linda.”

That would be Linda Belcher.

Johnson continues for the camera. He gives out Belcher’s home address. He claims that “the Islam’crat Barack Obama, criminal Clinton and lyin’ Linda have sent Chicago thugs” after him. His children and grandchild have been threatened, he says.

Just recently, Johnson claims in the video, his truck was roadblocked and ambushed, and his friend’s life threatened.

In the cadence of a seasoned preacher, Johnson says Belcher personally “killed” 80,000 babies — a warped reference to her stance on abortion. He says he heard Belcher’s shoes were stained red due to “all the blood of all those babies.”

He calls his critics “pygmies” and “Smurfs.” Toward the end of his five-minute screed, Johnson makes the stakes clear: This is a race that pits Donald Trump and Danny Ray Johnson against “criminal Hillary Clinton and lyin’ Linda Lou.”

His closing plea: “Let’s show ‘em that the good ol’ boys matter.”

![]()

Founded in 1796, Bullitt County got its name from Alexander Scott Bullitt, a leader in Kentucky’s early political formation. It sits on the far western end of the Bluegrass region and has a population of about 75,000, nearly 97 percent of whom are white.

The percentage of adults with a college degree is less than half the national average. A population boom began in the mid-1970s, after school desegregation and busing came to neighboring Jefferson County, home to Louisville.

Today, it’s not uncommon to see Confederate flags hanging from poles, porches and barns around Bullitt.

Belcher’s campaign couldn’t have been more different from that of her opponent. Her Facebook page featured no Confederate flags, no angry videos and no guns. Her listed interests included gardening, reading, civic activities, crafts and flower arranging.

She heard and saw Johnson’s slanderous boasts but didn’t want to take the bait. She doesn’t know any Chicago thugs, she said. She’s a Christian. “The last thing I would think of would be harming a church.”

Belcher wanted to focus on her own record.

“I’m more of a positive person,” she said. “People who want to believe garbage like that, I don’t know how you convince them otherwise.”

With Johnson’s social media campaign in full gear, some of his Facebook posts made news.

Media reports highlighted racist posts he shared. One image depicted Barack and Michelle Obama as cartoonish apes. Another showed a young chimpanzee with a caption, “Obama’s baby picture.” A third post showed former President Ronald Reagan feeding a small chimp a bottle. It was titled, “Reagan babysits a young Obama.”

Johnson dismissed the criticism. He said Facebook was “entertaining.” He claimed that the posts were simply satire and fair game.

Even his own party disagreed, urging him to withdraw from the race. The state’s GOP chair, Mac Brown, called the posts “outrageous” and the “rankest sort of prejudice.”

Johnson ignored all critics and continued to post and share exclusionary, nationalist, anti-Islam, racist posts. This country was in trouble, Johnson claimed, and needed help. He was the one to provide it.

On election night, Trump swamped Clinton in Bullitt County, winning nearly three-quarters of the vote. In the 49th District race, Johnson beat Belcher by 156 votes.

So, Johnson had reason to smile that night. He was on his way to the statehouse. He had weathered the Facebook controversy, in part because the most controversial posts were removed and his profile made private.

But other aspects of his past cannot be so readily erased.